Monuments and Square of Lucca

English Version

The Roman amphitheater, now buried about three meters, was built outside the walls in the 1st or 2nd century AD Elliptical in shape, it had two superimposed orders of fifty-five arches on pillars supporting the cavea, formed in turn by twenty steps and capable of ten thousand spectators. The building, which fell into disrepair during the barbarian invasions, became for centuries a sort of quarry for building materials: not surprisingly, during the Middle Ages it was referred to as "caves". In particular, the entire lining and all the columns were stripped. Later on the remaining ruins began to overlap houses and buildings that using the residual structures of the Amphitheater, perfectly preserved their shape. The current splendid square, unique and one of a kind, was built by the architect Nottolini (from 1830) who had some buildings demolished in the center demolished and created around it the street known as the Amphitheater.

L'anfiteatro romano, oggi interrato di circa tre metri, fu edificato fuori le mura nel I o II secolo d.C.. Di forma ellittica, aveva all'esterno due ordini sovrapposti di cinquantacinque arcate su pilastri che sorreggevano la cavea, formata a sua volta da venti gradini e capace di diecimila spettatori. L'edificio, andato in rovina durante le invasioni barbariche, diventò per secoli una specie di cava di materiali da costruzione: non a caso, durante il Medioevo era indicato col nome di "grotte". In particolare venne spogliato dell'intero rivestimento e di tutte le colonne. In seguito sui ruderi rimasti iniziarono a sovrapporsi case e costruzioni che utilizzando le residue strutture dell'Anfiteatro, ne conservarono perfettamente la forma. L'attuale splendida piazza, singolare ed unica nel suo genere, fu realizzata dall'architetto Nottolini (dal 1830) che fece abbattere alcune costruzioni sorte al centro e vi creò intorno la via detta appunto dell'Anfiteatro.

34 íbúar mæla með

Piazza Anfiteatro

Piazza dell'AnfiteatroEnglish Version

The Roman amphitheater, now buried about three meters, was built outside the walls in the 1st or 2nd century AD Elliptical in shape, it had two superimposed orders of fifty-five arches on pillars supporting the cavea, formed in turn by twenty steps and capable of ten thousand spectators. The building, which fell into disrepair during the barbarian invasions, became for centuries a sort of quarry for building materials: not surprisingly, during the Middle Ages it was referred to as "caves". In particular, the entire lining and all the columns were stripped. Later on the remaining ruins began to overlap houses and buildings that using the residual structures of the Amphitheater, perfectly preserved their shape. The current splendid square, unique and one of a kind, was built by the architect Nottolini (from 1830) who had some buildings demolished in the center demolished and created around it the street known as the Amphitheater.

L'anfiteatro romano, oggi interrato di circa tre metri, fu edificato fuori le mura nel I o II secolo d.C.. Di forma ellittica, aveva all'esterno due ordini sovrapposti di cinquantacinque arcate su pilastri che sorreggevano la cavea, formata a sua volta da venti gradini e capace di diecimila spettatori. L'edificio, andato in rovina durante le invasioni barbariche, diventò per secoli una specie di cava di materiali da costruzione: non a caso, durante il Medioevo era indicato col nome di "grotte". In particolare venne spogliato dell'intero rivestimento e di tutte le colonne. In seguito sui ruderi rimasti iniziarono a sovrapporsi case e costruzioni che utilizzando le residue strutture dell'Anfiteatro, ne conservarono perfettamente la forma. L'attuale splendida piazza, singolare ed unica nel suo genere, fu realizzata dall'architetto Nottolini (dal 1830) che fece abbattere alcune costruzioni sorte al centro e vi creò intorno la via detta appunto dell'Anfiteatro.

English Version

Ilaria del Carretto was the second wife of Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca between 1400 and 1430. After the premature death of the woman (she was only 25 years old), her husband commissioned the marble and stone sarcophagus from the sculptor Jacopo della Quercia , a funeral monument that required the sculptor two full years of work. The beautiful figure of Ilaria lies stretched out on a base decorated with cherubs and festoons, of classical inspiration. The head rests on a pillow, its eyes are closed and seems to be retracted in sleep. The dress is refined and elegant, with a particular shape, the garment adorned with a crown of fabric and flowers. The dog, nestled at his feet, symbolizes marital fidelity. The work, one of the greatest masterpieces of fifteenth-century sculpture, is the result of the extraordinary encounter between the late-Gothic taste of French descent of thin drapery and parallel folds, with the source of the Florentine taste of the sweet shape of the figure and face. . "... Jacopo, the lick of marble, tried to finish with infinite diligence," Giorgio Vasari said of him. Originally the work was located in the southern transept of the Cathedral of San Martino at a patronage altar of the Guinigi family between the funeral monument of Domenico Bertini (work by Matteo Civitali) and the corner pillar. The strip of floor with narrow and long stones that contrasts with the rest of the pavement, placed a short distance from the wall, is a fragment of the laying surface arranged to place Ilaria's monument. Here he remained until 1430, the year in which Paolo Guinigi was expelled from the city and all his assets were confiscated. Ilaria's sarcophagus was stripped of all those parts that referred to the tyrant: the slab with the emblem, later recovered, and a commemorative inscription, lost. In 1887, after having undergone various movements inside the church, the sarcophagus was recomposed in the north transept of the church, where it remained until its present location in the sacristy of the Cathedral. However, the funeral monument at Ilaria del Carretto, considered one of the best examples of Italian funerary sculpture of the fifteenth century, does not preserve the remains of Ilaria whose body rests in the chapel of Villa Guinigi.

Ilaria del Carretto è stata la seconda moglie di Paolo Guinigi, signore di Lucca tra il 1400 e il 1430. Dopo la morte prematura della donna (aveva infatti solo 25 anni), il marito commissionò allo scultore Jacopo della Quercia un sarcofago di marmo e pietra, un monumento funebre che richiese allo scultore due interi anni di lavorazione. La bella figura di Ilaria giace distesa su di un basamento decorato da putti e festoni, di ispirazione classica. La testa poggiata su di un cuscino, ha gli occhi chiusi e sembra essere ritratta nel sonno. La veste è raffinata ed elegante, con una foggia particolare, il capo ornato da una corona di stoffa e fiori. Il cane, accoccolato ai suoi piedi, simboleggia la fedeltà coniugale. L'opera, uno dei massimi capolavori della scultura quattrocentesca, è frutto dello straordinario incontro tra il gusto tardo-gotico di ascendenza francese del panneggio a pieghe sottili e parallele, con il sorgente gusto rinascimentale di ascendenza fiorentina del dolce modellato della figura e del volto. "... Jacopo di leccatezza pulitamente il marmo cercò di finire con diligenza infinita", disse di lui Giorgio Vasari. In origine l'opera era collocata nel transetto meridionale della Cattedrale di San Martino presso un altare patronato della famiglia Guinigi tra il Monumento funebre di Domenico Bertini (opera di Matteo Civitali) e il pilastro angolare. La striscia di pavimento con pietre strette e lunghe che contrasta col resto della pavimentazione, posta a poca distanza dal muro è un frammento del piano di posa predisposto per collocare il monumento di Ilaria. Qui rimase fino al 1430, anno in cui Paolo Guinigi venne cacciato dalla città e tutti i suoi beni furono confiscati. Il sarcofago di Ilaria venne spogliato di tutte quelle parti che facevano riferimento al tiranno: la lastra con lo stemma, poi recuperata, e un'iscrizione commemorativa, andata perduta. Nel 1887, dopo aver subito vari spostamenti all'interno della chiesa, il sarcofago fu ricomposto nel transetto nord della chiesa, dove è rimasto fino all'attuale collocazione nella sacrestia della Cattedrale. Il monumento funebre a Ilaria del Carretto, considerato tra i migliori esempi di scultura funeraria italiana del XV secolo non conserva però le spoglie di Ilaria la cui salma riposa nella cappella di Villa Guinigi.

Piazza Antelminelli

Piazza AntelminelliEnglish Version

Ilaria del Carretto was the second wife of Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca between 1400 and 1430. After the premature death of the woman (she was only 25 years old), her husband commissioned the marble and stone sarcophagus from the sculptor Jacopo della Quercia , a funeral monument that required the sculptor two full years of work. The beautiful figure of Ilaria lies stretched out on a base decorated with cherubs and festoons, of classical inspiration. The head rests on a pillow, its eyes are closed and seems to be retracted in sleep. The dress is refined and elegant, with a particular shape, the garment adorned with a crown of fabric and flowers. The dog, nestled at his feet, symbolizes marital fidelity. The work, one of the greatest masterpieces of fifteenth-century sculpture, is the result of the extraordinary encounter between the late-Gothic taste of French descent of thin drapery and parallel folds, with the source of the Florentine taste of the sweet shape of the figure and face. . "... Jacopo, the lick of marble, tried to finish with infinite diligence," Giorgio Vasari said of him. Originally the work was located in the southern transept of the Cathedral of San Martino at a patronage altar of the Guinigi family between the funeral monument of Domenico Bertini (work by Matteo Civitali) and the corner pillar. The strip of floor with narrow and long stones that contrasts with the rest of the pavement, placed a short distance from the wall, is a fragment of the laying surface arranged to place Ilaria's monument. Here he remained until 1430, the year in which Paolo Guinigi was expelled from the city and all his assets were confiscated. Ilaria's sarcophagus was stripped of all those parts that referred to the tyrant: the slab with the emblem, later recovered, and a commemorative inscription, lost. In 1887, after having undergone various movements inside the church, the sarcophagus was recomposed in the north transept of the church, where it remained until its present location in the sacristy of the Cathedral. However, the funeral monument at Ilaria del Carretto, considered one of the best examples of Italian funerary sculpture of the fifteenth century, does not preserve the remains of Ilaria whose body rests in the chapel of Villa Guinigi.

Ilaria del Carretto è stata la seconda moglie di Paolo Guinigi, signore di Lucca tra il 1400 e il 1430. Dopo la morte prematura della donna (aveva infatti solo 25 anni), il marito commissionò allo scultore Jacopo della Quercia un sarcofago di marmo e pietra, un monumento funebre che richiese allo scultore due interi anni di lavorazione. La bella figura di Ilaria giace distesa su di un basamento decorato da putti e festoni, di ispirazione classica. La testa poggiata su di un cuscino, ha gli occhi chiusi e sembra essere ritratta nel sonno. La veste è raffinata ed elegante, con una foggia particolare, il capo ornato da una corona di stoffa e fiori. Il cane, accoccolato ai suoi piedi, simboleggia la fedeltà coniugale. L'opera, uno dei massimi capolavori della scultura quattrocentesca, è frutto dello straordinario incontro tra il gusto tardo-gotico di ascendenza francese del panneggio a pieghe sottili e parallele, con il sorgente gusto rinascimentale di ascendenza fiorentina del dolce modellato della figura e del volto. "... Jacopo di leccatezza pulitamente il marmo cercò di finire con diligenza infinita", disse di lui Giorgio Vasari. In origine l'opera era collocata nel transetto meridionale della Cattedrale di San Martino presso un altare patronato della famiglia Guinigi tra il Monumento funebre di Domenico Bertini (opera di Matteo Civitali) e il pilastro angolare. La striscia di pavimento con pietre strette e lunghe che contrasta col resto della pavimentazione, posta a poca distanza dal muro è un frammento del piano di posa predisposto per collocare il monumento di Ilaria. Qui rimase fino al 1430, anno in cui Paolo Guinigi venne cacciato dalla città e tutti i suoi beni furono confiscati. Il sarcofago di Ilaria venne spogliato di tutte quelle parti che facevano riferimento al tiranno: la lastra con lo stemma, poi recuperata, e un'iscrizione commemorativa, andata perduta. Nel 1887, dopo aver subito vari spostamenti all'interno della chiesa, il sarcofago fu ricomposto nel transetto nord della chiesa, dove è rimasto fino all'attuale collocazione nella sacrestia della Cattedrale. Il monumento funebre a Ilaria del Carretto, considerato tra i migliori esempi di scultura funeraria italiana del XV secolo non conserva però le spoglie di Ilaria la cui salma riposa nella cappella di Villa Guinigi.

English Version

The large square dedicated to Napoleon, where stands the Palazzo Ducale, the seat of noble power since the times of Castruccio Castracani (XIV century) and Paolo Guinigi (XV century). The Piazza and the Palace are the result of the interventions desired in the first decades of the nineteenth century by Elisa Baciocchi, Napoleon's sister, and continued by Maria Luisa di Borbone and her son Carlo Lodovico, depicted in the monument by Lorenzo Bartolini located in the center of the Piazza

La grande Piazza dedicata a Napoleone, dove sorge il Palazzo Ducale, sede del potere signorile sin dai tempi di Castruccio Castracani (XIV secolo) e di Paolo Guinigi (XV secolo). La Piazza e il Palazzo sono frutto degli interventi voluti nei primi decenni dell’Ottocento da Elisa Baciocchi, sorella di Napoleone, e proseguiti da Maria Luisa di Borbone e dal figlio Carlo Lodovico, raffigurati nel monumento di Lorenzo Bartolini situato al centro della Piazza.

63 íbúar mæla með

Piazza Napoleone

Piazza NapoleoneEnglish Version

The large square dedicated to Napoleon, where stands the Palazzo Ducale, the seat of noble power since the times of Castruccio Castracani (XIV century) and Paolo Guinigi (XV century). The Piazza and the Palace are the result of the interventions desired in the first decades of the nineteenth century by Elisa Baciocchi, Napoleon's sister, and continued by Maria Luisa di Borbone and her son Carlo Lodovico, depicted in the monument by Lorenzo Bartolini located in the center of the Piazza

La grande Piazza dedicata a Napoleone, dove sorge il Palazzo Ducale, sede del potere signorile sin dai tempi di Castruccio Castracani (XIV secolo) e di Paolo Guinigi (XV secolo). La Piazza e il Palazzo sono frutto degli interventi voluti nei primi decenni dell’Ottocento da Elisa Baciocchi, sorella di Napoleone, e proseguiti da Maria Luisa di Borbone e dal figlio Carlo Lodovico, raffigurati nel monumento di Lorenzo Bartolini situato al centro della Piazza.

English Version

Piazza San Francesco, in the north-eastern part of the historic center a few steps away from the main streets and monuments, is a less known and crowded place, but equally rich in history and charm. The square is dominated by the Church of San Francesco built in 1228 by a small group of Franciscan friars who, two years after the death of the saint of Assisi and a few months before his canonization, received as a gift a plot of land with garden and hut in area then known as "Fratta" just outside the thirteenth century walls. Originally the church was dedicated to Santa Maria Maddalena and only in the course of the fourteenth century was dedicated to San Francesco. To this beautiful and austere brick church with a white façade is connected a large monastic complex that covers an area of over 12,000 square meters, with three bright cloisters around which the convent is organized. Near the church, another imposing building: Villa Guinigi, born as a summer residence and representative of Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca until 1430 and now home to the National Museum of Villa Guinigi: his rich collection of works of art tells the history of the city and the territory from the 13th century a.C to the eighteenth century. Crossing the whole square towards one of the most characteristic streets of the city, Via del Fosso, named for the moat that divides it for its entire length, leads to a particular intersection, where seven streets converge: here you can admire a monument so dear to Lucca, the Madonna dello Stellario. On a slender Corinthian order column, stands a beautiful statue of the Baroque Madonna, by sculptor Giovanni Lazzoni, placed on the summit in 1687. On the base a seventeenth-century view of Lucca, On the day of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December each year, the traditional floral tribute from the city to this is one of its most beloved symbols. Piazza San Francesco is today a living and dynamic reality, visited and appreciated by more and more people, residents and guests. Every Wednesday it is animated by the stalls of the organic peasant market where you can find only agricultural products strictly cultivated without pesticides: vegetables (including Slow Food presidia, the Canestrino tomato from Lucca and the Fagiolo rosso from Lucca), fresh fruit, raw milk cheese, cured meats, Cinta Senese pork meat, flour, bread and baked goods, oil, wine and honey. In the square or just a stone's throw away, in some of the best taverns in the city, you can enjoy a cuisine made of simple traditional dishes, chatting in good company in the cool spring and summer evenings sitting at outdoor tables.

Piazza San Francesco, nella zona nord orientale del centro storico a pochi passi dalle vie e dai monumenti principali, è un luogo meno conosciuto e affollato, ma ugualmente ricco di storia e suggestioni. La piazza è dominata dalla Chiesa di San Francesco costruita nel 1228 da un piccolo gruppo di frati francescani che, due anni dopo la morte del santo di Assisi e pochi mesi prima della sua canonizzazione, ricevettero in dono un appezzamento di terreno con orto e capanna nell'area nota allora come "Fratta" appena fuori le mure duecentesche. Originariamente la chiesa venne dedicata a Santa Maria Maddalena e solo nel corso del Trecento fu intitolata a San Francesco. A questa bella e austera chiesa in mattoni dalla bianca facciata è collegato un ampio complesso monastico che si estende su una superficie di oltre 12.000 metri quadrati, con tre luminosi chiostri intorno ai quali è organizzato il convento. In prossimità della chiesa, un altro imponente edificio: Villa Guinigi, nata come residenza estiva e di rappresentanza di Paolo Guinigi, signore di Lucca fino al 1430 e oggi sede del Museo nazionale di Villa Guinigi: la sua ricca collezione di opere d'arte racconta la storia della città e del territorio dal XIII sec. a.C al Settecento. Attraversando tutta la piazza verso una delle vie più caratteristiche della città, Via del Fosso, chiamata così per il fossato che la divide per la sua intera lunghezza, si arriva ad un incrocio particolare, dove confluiscono ben sette strade: qui si può ammirare un monumento tanto caro ai lucchesi, la Madonna dello Stellario. Su una slanciata colonna d'ordine corinzio, troneggia una bella statua della Madonna in stile barocco, opera dello scultore Giovanni Lazzoni, collocata sulla sommità nel 1687. Sul basamento una veduta seicentesca di Lucca, Nel giorno dell’Immacolata Concezione, l’8 dicembre di ogni anno, ha luogo il tradizionale omaggio floreale da parte della città a questo che è uno dei suoi simboli più amati. Piazza San Francesco è oggi una realtà viva e dinamica, visitata e apprezzata da sempre più persone, residenti e ospiti. Ogni mercoledì è animata dai banchi del mercato contadino biologico dove si possono trovare solo prodotti agricoli coltivati rigorosamente senza pesticidi: ortaggi (anche presidi Slow Food, il Pomodoro canestrino di Lucca e il Fagiolo rosso di Lucca), frutta fresca, formaggio a latte crudo, salumi, carni di razza suina Cinta senese, farine, pane e prodotti da forno, olio, vino e miele. Nella piazza o giusto a due passi di distanza, in alcune delle migliori osterie della città, è possibile gustare una cucina fatta di piatti semplici della tradizione, chiacchierando in buona compagnia nelle fresche serate primaverili ed estive seduti ai tavoli all'aperto.

Piazza S.Francesco

Piazza S.FrancescoEnglish Version

Piazza San Francesco, in the north-eastern part of the historic center a few steps away from the main streets and monuments, is a less known and crowded place, but equally rich in history and charm. The square is dominated by the Church of San Francesco built in 1228 by a small group of Franciscan friars who, two years after the death of the saint of Assisi and a few months before his canonization, received as a gift a plot of land with garden and hut in area then known as "Fratta" just outside the thirteenth century walls. Originally the church was dedicated to Santa Maria Maddalena and only in the course of the fourteenth century was dedicated to San Francesco. To this beautiful and austere brick church with a white façade is connected a large monastic complex that covers an area of over 12,000 square meters, with three bright cloisters around which the convent is organized. Near the church, another imposing building: Villa Guinigi, born as a summer residence and representative of Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca until 1430 and now home to the National Museum of Villa Guinigi: his rich collection of works of art tells the history of the city and the territory from the 13th century a.C to the eighteenth century. Crossing the whole square towards one of the most characteristic streets of the city, Via del Fosso, named for the moat that divides it for its entire length, leads to a particular intersection, where seven streets converge: here you can admire a monument so dear to Lucca, the Madonna dello Stellario. On a slender Corinthian order column, stands a beautiful statue of the Baroque Madonna, by sculptor Giovanni Lazzoni, placed on the summit in 1687. On the base a seventeenth-century view of Lucca, On the day of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December each year, the traditional floral tribute from the city to this is one of its most beloved symbols. Piazza San Francesco is today a living and dynamic reality, visited and appreciated by more and more people, residents and guests. Every Wednesday it is animated by the stalls of the organic peasant market where you can find only agricultural products strictly cultivated without pesticides: vegetables (including Slow Food presidia, the Canestrino tomato from Lucca and the Fagiolo rosso from Lucca), fresh fruit, raw milk cheese, cured meats, Cinta Senese pork meat, flour, bread and baked goods, oil, wine and honey. In the square or just a stone's throw away, in some of the best taverns in the city, you can enjoy a cuisine made of simple traditional dishes, chatting in good company in the cool spring and summer evenings sitting at outdoor tables.

Piazza San Francesco, nella zona nord orientale del centro storico a pochi passi dalle vie e dai monumenti principali, è un luogo meno conosciuto e affollato, ma ugualmente ricco di storia e suggestioni. La piazza è dominata dalla Chiesa di San Francesco costruita nel 1228 da un piccolo gruppo di frati francescani che, due anni dopo la morte del santo di Assisi e pochi mesi prima della sua canonizzazione, ricevettero in dono un appezzamento di terreno con orto e capanna nell'area nota allora come "Fratta" appena fuori le mure duecentesche. Originariamente la chiesa venne dedicata a Santa Maria Maddalena e solo nel corso del Trecento fu intitolata a San Francesco. A questa bella e austera chiesa in mattoni dalla bianca facciata è collegato un ampio complesso monastico che si estende su una superficie di oltre 12.000 metri quadrati, con tre luminosi chiostri intorno ai quali è organizzato il convento. In prossimità della chiesa, un altro imponente edificio: Villa Guinigi, nata come residenza estiva e di rappresentanza di Paolo Guinigi, signore di Lucca fino al 1430 e oggi sede del Museo nazionale di Villa Guinigi: la sua ricca collezione di opere d'arte racconta la storia della città e del territorio dal XIII sec. a.C al Settecento. Attraversando tutta la piazza verso una delle vie più caratteristiche della città, Via del Fosso, chiamata così per il fossato che la divide per la sua intera lunghezza, si arriva ad un incrocio particolare, dove confluiscono ben sette strade: qui si può ammirare un monumento tanto caro ai lucchesi, la Madonna dello Stellario. Su una slanciata colonna d'ordine corinzio, troneggia una bella statua della Madonna in stile barocco, opera dello scultore Giovanni Lazzoni, collocata sulla sommità nel 1687. Sul basamento una veduta seicentesca di Lucca, Nel giorno dell’Immacolata Concezione, l’8 dicembre di ogni anno, ha luogo il tradizionale omaggio floreale da parte della città a questo che è uno dei suoi simboli più amati. Piazza San Francesco è oggi una realtà viva e dinamica, visitata e apprezzata da sempre più persone, residenti e ospiti. Ogni mercoledì è animata dai banchi del mercato contadino biologico dove si possono trovare solo prodotti agricoli coltivati rigorosamente senza pesticidi: ortaggi (anche presidi Slow Food, il Pomodoro canestrino di Lucca e il Fagiolo rosso di Lucca), frutta fresca, formaggio a latte crudo, salumi, carni di razza suina Cinta senese, farine, pane e prodotti da forno, olio, vino e miele. Nella piazza o giusto a due passi di distanza, in alcune delle migliori osterie della città, è possibile gustare una cucina fatta di piatti semplici della tradizione, chiacchierando in buona compagnia nelle fresche serate primaverili ed estive seduti ai tavoli all'aperto.

English Version

Piazza San Michele has always been the heart of the historic center of Lucca, the natural outlet of an intricate tangle of narrow streets and alleys that come from the various corners of the city: many different points of view depending on the multiple entrances leading to the square. It stands on the site of the ancient Roman forum, at the perfect intersection of the two main roads: the Cardo Massimo (from north to south, corresponding to the current Via Fillungo, Via Cenami and Via S. Giovanni) and the Decumanus Maximus (from west to east , today's Via S. Paolino, Via Roma and Via S. Croce). From the origins, center of the administrative, political and religious power of the Roman colony, at the heart of the medieval city. Lucca became the capital of silk in Europe in the Middle Ages and with the development of processing techniques and trade, the square became the place of passage where to do business and meet people. Even the foreigner is seen as an opportunity for money changers and silk merchant shops: in the city one comes to buy and sell, repair or commission work. Unfortunately, few of the buildings of the time have survived, but they are easily recognizable by the architecture of the buildings on the sides of the square, with their pointed and pointed arches, brick facades and mullioned windows.

In the north-east corner of the square, attention is captured by the Church of San Michele in Foro in Romanesque style with elements of Gothic taste. The works of its construction, documented as early as the 8th century, were prolonged for a long time and the transition to later periods created a complex work characterized by a contrast of different styles. On the top of the facade of the church, another jewel does not go unnoticed: the majestic marble statue of the Archangel Michael, victorious while piercing a dragon with a sword. In the Renaissance period the square continued to be the political and business center as evidenced by the new imposing buildings that were erected there: on the corner with Via Vittorio Veneto, Palazzo Pretorio, built in 1492, at the time the seat of authority and its offices judicial. Palazzo Gigli, built in 1529 on medieval housing structures, which today houses a bank branch. Under his large loggia there are some works of art linked to famous people from Lucca, such as the bronze statue of the sculptor and architect Matteo Civitali and the bust of explorer Carlo Piaggia. The loggia of the palace itself often hosts contemporary art exhibitions and food and wine events. A particularly fine watch enriches the upper part of the facade. In the 18th century the pavement of Piazza San Michele, paved with herringbone bricks in the 15th century at the time of the construction of Palazzo Pretorio, was raised with squares of gray stone and surrounded by marble columns joined by metal chains. So we still see it today. In 1863 in honor of Francesco Burlamacchi, an important 16th century politician from Lucca, the statue by the sculptor Ulisse Cambi was placed in the center of the square. The testimonies of its long history are visible even in small, apparently banal details, such as the old signs of the early 20th century of the still open pharmacies, or the liberty style puttini found above the shop windows on the west side of the square. Today it continues to be the heart of the city, a meeting and entertainment point for the Lucchese and visiting guests. From the tables of the bars overlooking the square, the view is spectacular from every shot. In a historic pastry shop (since 1881) just behind the church bell tower, comfortably seated outside or in its characteristic interior with antique furniture, you can pamper yourself by sipping a cappuccino, a tea or a chocolate. Those with a sweet tooth can also enjoy the typical sweets of the city, such as the delicious "Coi Becchi" cakes and the famous Buccellato, which has received numerous awards all over the world, including the review by the New York Times gastronomy and critic, Mimi Sheraton, who included it in his book, "The 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die".

Piazza San Michele è da sempre il cuore del centro storico di Lucca, lo sbocco naturale di un intricato groviglio di stradine e viuzze che provengono dai vari angoli della città: tanti punti di vista diversi a seconda dei molteplici ingressi che portano alla piazza. Sorge sul luogo dell'antico foro romano, all'incrocio perfetto delle due strade principali: il Cardo Massimo (da nord a sud, corrispondente alle attuali Via Fillungo, Via Cenami e Via S. Giovanni) e il Decumano Massimo (da ovest ad est, le odierne Via S. Paolino, Via Roma e Via S. Croce).

Dalle origini, centro del potere amministrativo, politico e religioso della colonia romana, a cuore della città medievale. Lucca diventa nel Medioevo la capitale della seta in Europa e con lo sviluppo delle tecniche di lavorazione e dei commerci, la piazza diventa il luogo di passaggio dove fare affari e incontrare persone. Ai banchi dei cambiavalute e nelle botteghe dei mercanti di tessuti di seta, anche lo straniero è visto come un’opportunità: in città si viene per comprare e vendere, riparare o commissionare lavori. Sono purtroppo poche le costruzioni dell'epoca arrivate fino a noi, ma facilmente riconoscibili dalle architetture dei palazzi ai lati della piazza, con i loro archi a tutto sesto e sesto acuto, i paramenti in mattoni e le finestre polifore.

Nell'angolo nord-est della piazza, l'attenzione è catturata dalla Chiesa di San Michele in Foro in stile romanico con elementi di gusto gotico. I lavori della sua costruzione, documentati già nel VIII secolo, furono protratti a lungo nel tempo e il passaggio a epoche successive ha creato un'opera complessa caratterizzata da una contrapposizione di diversi stili. Sulla sommità della facciata della chiesa, un altro gioiello non passa inosservato: la maestosa statua in marmo dell'Arcangelo Michele, vittorioso mentre trafigge un drago con la spada. Nel periodo rinascimentale la piazza continuò ad essere il centro politico e degli affari come testimoniano i nuovi imponenti edifici che vi vennero innalzati: all'angolo con Via Vittorio Veneto, Palazzo Pretorio, edificato nel 1492, all'epoca sede del potestà e dei suoi uffici giudiziari. Palazzo Gigli, costruito nel 1529 su strutture di abitazioni medievali, che oggi ospita la filiale di una banca. Sotto la sua ampia loggia trovano posto alcune opere d'arte legate a celebri personaggi lucchesi, come la statua in bronzo dello scultore e architetto Matteo Civitali e il busto dell'esploratore Carlo Piaggia. La stessa loggia del palazzo ospita spesso mostre di arte contemporanea e manifestazioni enogastronomiche. Un orologio di particolare pregio arricchisce la parte superiore della facciata. Nel '700 la pavimentazione di Piazza San Michele, lastricata con mattoni a spina di pesce nel '400 all'epoca della costruzione di Palazzo Pretorio, fu rialzata con quadroni di pietra grigia e circondata da colonnine marmoree unite da catene metalliche. Così la vediamo ancora oggi. Nel 1863 in onore di Francesco Burlamacchi, importante uomo politico lucchese del XVI secolo, fu collocata al centro della piazza la statua realizzata dallo scultore Ulisse Cambi. Le testimonianze della sua lunga storia sono visibili anche in piccoli particolari apparentemente banali, come le vecchie insegne di inizio '900 delle farmacie ancora aperte, o i puttini in stile liberty che si trovano sopra le vetrine dei negozi sul lato ovest della piazza. Oggi continua ad essere il cuore della città, punto di incontro e svago per i lucchesi e gli ospiti in visita. Dai tavolini dei bar affacciati sulla piazza, la vista è spettacolare da ogni inquadratura. In una storica pasticceria (dal 1881) proprio dietro il campanile della chiesa, comodamente seduti all'esterno o nel suo caratteristico interno con mobili d'epoca, ci si può coccolare sorseggiando un cappuccino, un thè o una cioccolata. I più golosi possono gustare anche i dolci tipici della città, come le prelibate torte "Coi Becchi" e il famoso Buccellato, che ha ottenuto numerosi riconoscimenti in tutto il mondo, fra i quali la recensione della gastronoma e critica del New York Times, Mimi Sheraton, che lo ha inserito nel suo libro, "I 1000 cibi da mangiare prima di morire".

91 íbúar mæla með

Piazza San Michele

Piazza San MicheleEnglish Version

Piazza San Michele has always been the heart of the historic center of Lucca, the natural outlet of an intricate tangle of narrow streets and alleys that come from the various corners of the city: many different points of view depending on the multiple entrances leading to the square. It stands on the site of the ancient Roman forum, at the perfect intersection of the two main roads: the Cardo Massimo (from north to south, corresponding to the current Via Fillungo, Via Cenami and Via S. Giovanni) and the Decumanus Maximus (from west to east , today's Via S. Paolino, Via Roma and Via S. Croce). From the origins, center of the administrative, political and religious power of the Roman colony, at the heart of the medieval city. Lucca became the capital of silk in Europe in the Middle Ages and with the development of processing techniques and trade, the square became the place of passage where to do business and meet people. Even the foreigner is seen as an opportunity for money changers and silk merchant shops: in the city one comes to buy and sell, repair or commission work. Unfortunately, few of the buildings of the time have survived, but they are easily recognizable by the architecture of the buildings on the sides of the square, with their pointed and pointed arches, brick facades and mullioned windows.

In the north-east corner of the square, attention is captured by the Church of San Michele in Foro in Romanesque style with elements of Gothic taste. The works of its construction, documented as early as the 8th century, were prolonged for a long time and the transition to later periods created a complex work characterized by a contrast of different styles. On the top of the facade of the church, another jewel does not go unnoticed: the majestic marble statue of the Archangel Michael, victorious while piercing a dragon with a sword. In the Renaissance period the square continued to be the political and business center as evidenced by the new imposing buildings that were erected there: on the corner with Via Vittorio Veneto, Palazzo Pretorio, built in 1492, at the time the seat of authority and its offices judicial. Palazzo Gigli, built in 1529 on medieval housing structures, which today houses a bank branch. Under his large loggia there are some works of art linked to famous people from Lucca, such as the bronze statue of the sculptor and architect Matteo Civitali and the bust of explorer Carlo Piaggia. The loggia of the palace itself often hosts contemporary art exhibitions and food and wine events. A particularly fine watch enriches the upper part of the facade. In the 18th century the pavement of Piazza San Michele, paved with herringbone bricks in the 15th century at the time of the construction of Palazzo Pretorio, was raised with squares of gray stone and surrounded by marble columns joined by metal chains. So we still see it today. In 1863 in honor of Francesco Burlamacchi, an important 16th century politician from Lucca, the statue by the sculptor Ulisse Cambi was placed in the center of the square. The testimonies of its long history are visible even in small, apparently banal details, such as the old signs of the early 20th century of the still open pharmacies, or the liberty style puttini found above the shop windows on the west side of the square. Today it continues to be the heart of the city, a meeting and entertainment point for the Lucchese and visiting guests. From the tables of the bars overlooking the square, the view is spectacular from every shot. In a historic pastry shop (since 1881) just behind the church bell tower, comfortably seated outside or in its characteristic interior with antique furniture, you can pamper yourself by sipping a cappuccino, a tea or a chocolate. Those with a sweet tooth can also enjoy the typical sweets of the city, such as the delicious "Coi Becchi" cakes and the famous Buccellato, which has received numerous awards all over the world, including the review by the New York Times gastronomy and critic, Mimi Sheraton, who included it in his book, "The 1000 Foods to Eat Before You Die".

Piazza San Michele è da sempre il cuore del centro storico di Lucca, lo sbocco naturale di un intricato groviglio di stradine e viuzze che provengono dai vari angoli della città: tanti punti di vista diversi a seconda dei molteplici ingressi che portano alla piazza. Sorge sul luogo dell'antico foro romano, all'incrocio perfetto delle due strade principali: il Cardo Massimo (da nord a sud, corrispondente alle attuali Via Fillungo, Via Cenami e Via S. Giovanni) e il Decumano Massimo (da ovest ad est, le odierne Via S. Paolino, Via Roma e Via S. Croce).

Dalle origini, centro del potere amministrativo, politico e religioso della colonia romana, a cuore della città medievale. Lucca diventa nel Medioevo la capitale della seta in Europa e con lo sviluppo delle tecniche di lavorazione e dei commerci, la piazza diventa il luogo di passaggio dove fare affari e incontrare persone. Ai banchi dei cambiavalute e nelle botteghe dei mercanti di tessuti di seta, anche lo straniero è visto come un’opportunità: in città si viene per comprare e vendere, riparare o commissionare lavori. Sono purtroppo poche le costruzioni dell'epoca arrivate fino a noi, ma facilmente riconoscibili dalle architetture dei palazzi ai lati della piazza, con i loro archi a tutto sesto e sesto acuto, i paramenti in mattoni e le finestre polifore.

Nell'angolo nord-est della piazza, l'attenzione è catturata dalla Chiesa di San Michele in Foro in stile romanico con elementi di gusto gotico. I lavori della sua costruzione, documentati già nel VIII secolo, furono protratti a lungo nel tempo e il passaggio a epoche successive ha creato un'opera complessa caratterizzata da una contrapposizione di diversi stili. Sulla sommità della facciata della chiesa, un altro gioiello non passa inosservato: la maestosa statua in marmo dell'Arcangelo Michele, vittorioso mentre trafigge un drago con la spada. Nel periodo rinascimentale la piazza continuò ad essere il centro politico e degli affari come testimoniano i nuovi imponenti edifici che vi vennero innalzati: all'angolo con Via Vittorio Veneto, Palazzo Pretorio, edificato nel 1492, all'epoca sede del potestà e dei suoi uffici giudiziari. Palazzo Gigli, costruito nel 1529 su strutture di abitazioni medievali, che oggi ospita la filiale di una banca. Sotto la sua ampia loggia trovano posto alcune opere d'arte legate a celebri personaggi lucchesi, come la statua in bronzo dello scultore e architetto Matteo Civitali e il busto dell'esploratore Carlo Piaggia. La stessa loggia del palazzo ospita spesso mostre di arte contemporanea e manifestazioni enogastronomiche. Un orologio di particolare pregio arricchisce la parte superiore della facciata. Nel '700 la pavimentazione di Piazza San Michele, lastricata con mattoni a spina di pesce nel '400 all'epoca della costruzione di Palazzo Pretorio, fu rialzata con quadroni di pietra grigia e circondata da colonnine marmoree unite da catene metalliche. Così la vediamo ancora oggi. Nel 1863 in onore di Francesco Burlamacchi, importante uomo politico lucchese del XVI secolo, fu collocata al centro della piazza la statua realizzata dallo scultore Ulisse Cambi. Le testimonianze della sua lunga storia sono visibili anche in piccoli particolari apparentemente banali, come le vecchie insegne di inizio '900 delle farmacie ancora aperte, o i puttini in stile liberty che si trovano sopra le vetrine dei negozi sul lato ovest della piazza. Oggi continua ad essere il cuore della città, punto di incontro e svago per i lucchesi e gli ospiti in visita. Dai tavolini dei bar affacciati sulla piazza, la vista è spettacolare da ogni inquadratura. In una storica pasticceria (dal 1881) proprio dietro il campanile della chiesa, comodamente seduti all'esterno o nel suo caratteristico interno con mobili d'epoca, ci si può coccolare sorseggiando un cappuccino, un thè o una cioccolata. I più golosi possono gustare anche i dolci tipici della città, come le prelibate torte "Coi Becchi" e il famoso Buccellato, che ha ottenuto numerosi riconoscimenti in tutto il mondo, fra i quali la recensione della gastronoma e critica del New York Times, Mimi Sheraton, che lo ha inserito nel suo libro, "I 1000 cibi da mangiare prima di morire".

English Version

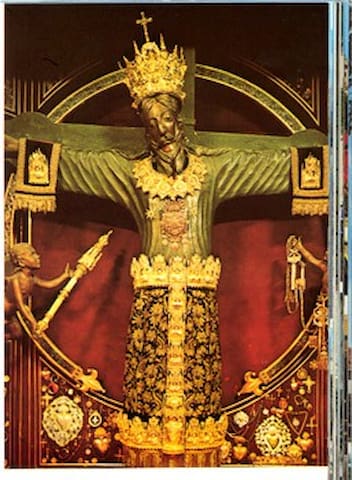

The Holy Face is a walnut crucifix, a reliquary statue that is found inside the Cathedral of San Martino. The crucifix has been a pilgrimage destination since the Middle Ages; pilgrims from all over the world have come to Lucca to admire the statue that, according to the legend of Leobino, was sculpted by Nicodemus after the resurrection and ascension of Christ. (A fresco by the painter Amico Aspertini depicting the legend, is preserved in the Chapel of San Agostino inside the basilica of San Frediano.) His effigy became the symbol of the city of Lucca so much that it was placed on the seals of the traders and on coins. Every year on September 13th the evocative Holy Face procession (Luminara di Santa Croce) takes place on the same itinerary, starting from the Basilica of San Frediano around 8.00 pm and arriving at the Cathedral of San Martino, where the Blessing is given and the traditional Mottettone is performed (a choral and instrumental polyphonic composition, composed year by year by Lucchese musicians).

Il Volto Santo è un crocifisso in legno di noce, una statua reliquario che si trova all’interno della cattedrale di San Martino. Il crocifisso è stato, sin dal medioevo, meta di pellegrinaggi; pellegrini da tutto il mondo sono infatti giunti a Lucca per ammirare la statua che, secondo la leggenda di Leobino, fu scolpita da Nicodemo dopo la resurrezione e l’ascensione di Cristo. (Un’affresco del pittore Amico Aspertini che raffigura la leggenda, è conservato nella Cappella di San Agostino all’interno della basilica di San Frediano.) La sua effige divenne il simbolo della città di Lucca tanto che fu posta sui sigilli dei cambisti e sulle monete. Il 13 Settembre di ogni anno si svolge la suggestiva processione del Volto Santo (Luminara di Santa Croce) che ripercorre lo stesso itinerario, con partenza dalla Basilica di San Frediano intorno alle 20.00 e arrivo alla Cattedrale di San Martino, dove viene impartita la Benedizione e viene eseguito il tradizionale Mottettone (una composizione polifonica di tipo corale e strumentale, composta anno per anno da musicisti lucchesi).

109 íbúar mæla með

St Martin dómkirkja

Piazza AntelminelliEnglish Version

The Holy Face is a walnut crucifix, a reliquary statue that is found inside the Cathedral of San Martino. The crucifix has been a pilgrimage destination since the Middle Ages; pilgrims from all over the world have come to Lucca to admire the statue that, according to the legend of Leobino, was sculpted by Nicodemus after the resurrection and ascension of Christ. (A fresco by the painter Amico Aspertini depicting the legend, is preserved in the Chapel of San Agostino inside the basilica of San Frediano.) His effigy became the symbol of the city of Lucca so much that it was placed on the seals of the traders and on coins. Every year on September 13th the evocative Holy Face procession (Luminara di Santa Croce) takes place on the same itinerary, starting from the Basilica of San Frediano around 8.00 pm and arriving at the Cathedral of San Martino, where the Blessing is given and the traditional Mottettone is performed (a choral and instrumental polyphonic composition, composed year by year by Lucchese musicians).

Il Volto Santo è un crocifisso in legno di noce, una statua reliquario che si trova all’interno della cattedrale di San Martino. Il crocifisso è stato, sin dal medioevo, meta di pellegrinaggi; pellegrini da tutto il mondo sono infatti giunti a Lucca per ammirare la statua che, secondo la leggenda di Leobino, fu scolpita da Nicodemo dopo la resurrezione e l’ascensione di Cristo. (Un’affresco del pittore Amico Aspertini che raffigura la leggenda, è conservato nella Cappella di San Agostino all’interno della basilica di San Frediano.) La sua effige divenne il simbolo della città di Lucca tanto che fu posta sui sigilli dei cambisti e sulle monete. Il 13 Settembre di ogni anno si svolge la suggestiva processione del Volto Santo (Luminara di Santa Croce) che ripercorre lo stesso itinerario, con partenza dalla Basilica di San Frediano intorno alle 20.00 e arrivo alla Cattedrale di San Martino, dove viene impartita la Benedizione e viene eseguito il tradizionale Mottettone (una composizione polifonica di tipo corale e strumentale, composta anno per anno da musicisti lucchesi).